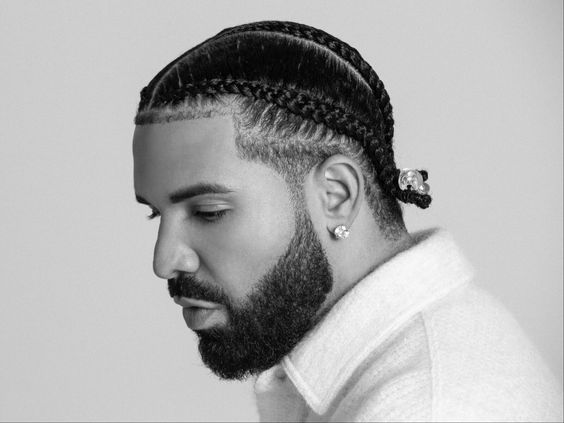

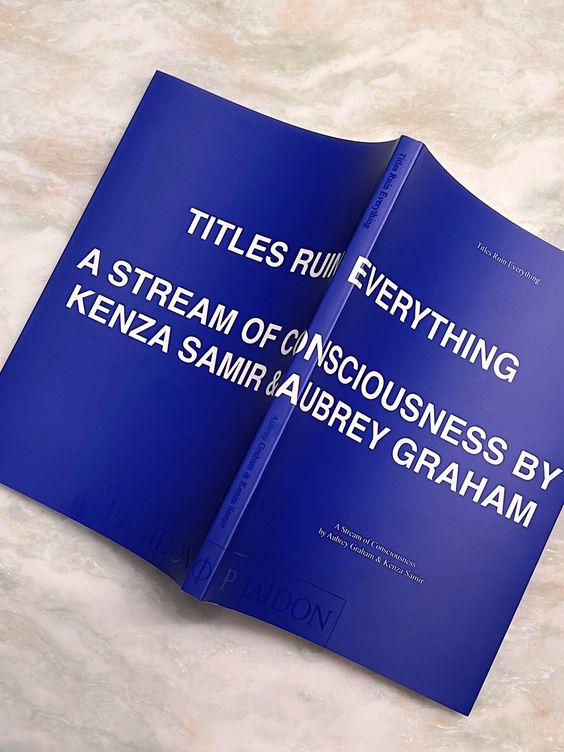

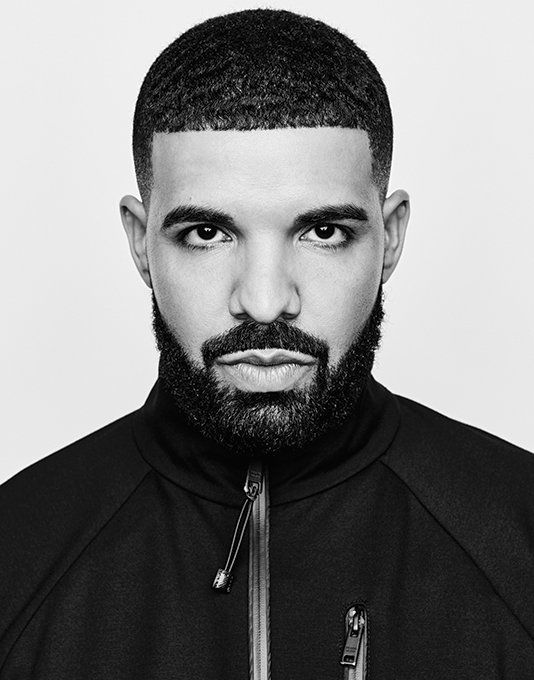

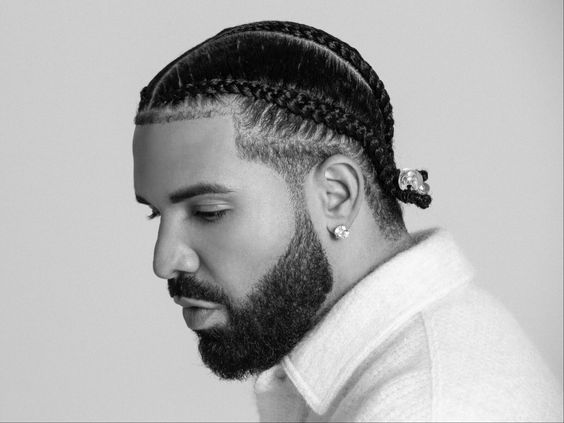

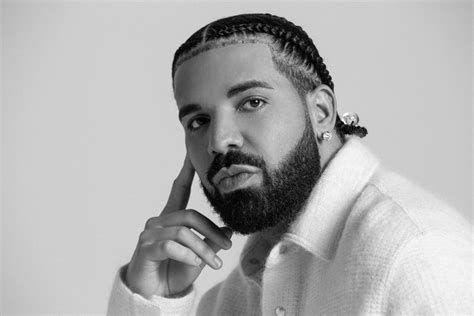

“I don’t know if I have ever wanted people to buy or support something more in my life,” Drake wrote in his post alongside a photo of a blue book covered in title text from the back to the front cover.

“I don’t know if I have ever wanted people to buy or support something more in my life,” Drake wrote in his post alongside a photo of a blue book covered in title text from the back to the front cover.

Titles Ruin Everything is the new offering from Aubrey Graham and longtime songwriting and composing partner Kenza Samir. Kenza Samir is a songwriter who has been credited on several Drake albums. Drake’s book was published by Phaidon Press out of London. The poetry book opens with a QR code that reveals a statement from The Boy himself: “I made an album to go with the book. They say they miss the old Drake girl don’t tempt me. FOR ALL THE DOGS.”

The dimensions of the collection are 5.75 x 8.25 inches – but no information about its contents is listed. A Drake paint marker inspires a more detailed description. Like a sought-after pair of shoes, the collection sold out instantly upon its publication at the end of June.

Titles Ruin Everything is 168 pages long. On each of those pages, save for a few blanks scattered throughout, there is a half-baked half-joke about celebrity, riches, or relationships. Sometimes, two side-by-side pages work in tandem to form a semi-compelling thought (“My therapist told me I need to stop listening to what people tell me/but if I take her advice wouldn’t I be listening to what people tell me?”). Other thoughts are, well, less compelling (“There are two types of women in this world,/women who like giving head and women who I don’t like”), or not compelling at all (“Dead serious/till I die”).

Drake’s poem book is similarly social media-friendly. Each of his poems consists of a line or two at the center of the page in a typewriter-like font. They often contain casual misogyny and braggadocio: “My talents include a pen. Your talents include a bed…/We’re both skilled nonetheless”. Some hardly make sense: “If jumping to conclusions was an Olympic sport/You wouldn’t have just won my heart, you would have won gold”.

The 36-year-old Canadian rapper has five Grammys and is one of the most listened-to artists on Spotify, but clearly music wasn’t keeping Drake busy enough. Drake’s poetry book collection reads as his own take on Rupi Kaur’s best-selling 2014 book Milk and Honey, the pioneering text of “Instapoetry”. This genre is characterized by short lines, often in aesthetically pleasing fonts, rendering these poems highly compatible with sharing on Instagram. While Milk and Honey was a commercial hit, with 3 million copies sold globally to date, it has been critically derided as shallow and trite.

Hanif Abdurraqib, the New York Times best-selling author behind Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, called the poems “silly lil’ jokes.”

“Some of these are so absurd that they’re actually funny,” he said. “But it’s hard to tell if he also understands that they’re bending into absurdist humor, and understands that there will be people who find it profound? Or if he’s convinced himself of the profundity. Really, it’s kind of just a book of puns. Silly lil’ jokes.”

Houston poet Aris Kian also criticized the book for its “petty abstractions.”

“Where he could push himself to indulge in the silliness and sentimentality that even the purest of poets would forgive, he disintegrates into petty abstractions and instead gives us lines like, ‘You were in my dream last night/ They call that a nightmare, right?’” she said.

“Drake’s poems operate within an excess of white space, a reduced set of images and limited punctuation. The tools of tension, breath and play are only explored through the typical two-line set up/punchline format.”

Drake’s relationship with his audience, especially those harder to please, has become a lot like the relationships he portrays with various women: more rooted in an ongoing push-and-pull than a consistent product, be it steamy romance, genuine vulnerability, or concrete catharsis. Even when he misses, the promise—spoken or unspoken—is that he will be back, and the exchange will be better.

When a musician of Drake’s stature publishes a work of literature, it often comes across as something they are taking seriously, and want you to take seriously, too. Removed from distractions like earworm production, beefy dramatics, and the maintenance of musical legacy, their words exist on blank pages with few options but to be genuine—whether because they’re true, or because they’re rooted in feelings that are. The thing about Titles Ruin Everything, and the paranoid hip-hop despot behind it, is that as real as these sentiments may be, they aren’t really that interesting unless your name is Aubrey Graham. Much like his recent music, there are two ways you can read this book: with disappointment, or with the tentative, half-smiling nods of someone who cannot relate, but would love to pretend they can.